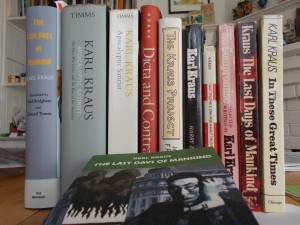

After decades of dribs and drabs, we are suddenly awash in English translations of Karl Kraus, the Viennese writer who’s been an on and off obsession of mine since I was a teenager. I became aware of Kraus through reading Schoenberg’s letters, Style and Idea, and Webern’s lectures published as The Path To The New Music. Reading things associated with Wittgenstein, Ernst Krenek, Freud – Kraus’s name seemed to come up a lot.

Sometime in college I read, in quick succession, Elias Canetti’s memoir trilogy, Carl Schorske’s Fin-de-siecle Vienna, and Wittgentstein’s Vienna by Stephane Toulmin and Allan Janik. Suddenly I saw Kraus as the link between the brilliant austerity of Webern and Wittgenstein’s Tractatus, the polemics and pedagogics of Schoenberg, and the politics of … well, I wanted them to be my politics. I somewhat naively understood Kraus to be the stridentist of scourges of the nascent military industrial complex and of the press’s complicitness in it. That seemed pretty good to me! Oh sure, he was a little anti-Semitic in the early years, but weren’t they all?

When T.J. Kirk was playing at the Elbow Room in Chicago, around 1994, I went to Powell’s Books across the street after sound check and found Edward Timms’s groundbreaking study of Kraus, Apocalyptic Satirist. A book about Kraus by a serious historian! This book gave me a much needed introduction to the evolution and context of Kraus’s politics (some of which I should probably have remembered from Schorske).

And then twenty years went by with next to nothing by or about Kraus in English. Finally in 2005 Timms’ second volume came out, covering the later decades of Kraus’s life, during the rise of Nazism. I began to wonder why I was into Kraus – he was so strident, so self-absorbed, so combative, vitriolic. He treated a young woman as an object of his possession, to be shared with other friends. His anti-Semitism was more intense than I had realized, and it lingered longer than I had realized. My admiration for these Viennese lunatics – Wittgenstein, Schenker, Kraus, Schiele – was really starting to pale.

First in the recent spate was Jonathan Franzen’s The Kraus Project. I enjoyed this improbable book immensely, and enjoyed reading some of the eyerolls it got in reviews as well. I think I had a smile on my face the whole time I was reading it, a smile that said “I can’t get over that this famous American intellectual has published a book about Karl F-ing Kraus! What’s next, Neil deGrasse Tyson setting up a foundation for the promotion of Laura Riding?”

Of course on inspection it makes all the sense in the world that Kraus would resonate with Franzen. I thought his exposition of Kraus’s polemic against Heine and his champions, and for Nestroy, was cogent and well-contextualized for contemporary American readers, like moi. I loved that there was a cranky, personal book about Kraus that nevertheless also delivered some major front and center Kraus stuff – two important essays that weren’t in English before.

After Franzen, the deluge: there have now emerged, from separate monkeys in separate caves with separate typewriters, three complete English translations of Kraus’s 600 page epic play/collage/poem Die letzten Tage der Menschheit, The Last Days Of Mankind. Only fragments had heretofore been available in English (and these long out of print) and those selections were dangerously unrepresentative, excising Kraus’s anti-Semitic characterizations of Viennese Jews both powerful and powerless.

First into solid book form was the translation of Fred Brigham and Edward Timms, published by Yale University Press. Timms is the author of the comprehensive two volume study of Kraus, Apocalyptic Satirist, and probably knows more than anyone else in the English speaking world about Kraus and his contemporaries, so you would expect this to be pretty much definitive.

The polymathic English author Michael Russell, in collaboration with Cordelia von Klot, has been working on a translation of Die letzten Tage for several years, and I would estimate about a quarter of the text is already available on thelastdaysofmankind.com. In addition the site has Klot’s “Complete Working Translation” of the work. Russell: “I asked Cordelia to produce an over-literal, even clumsily literal translation for use as a tool in translation. It is best used as a tool for those reading the German, especially students, whose German will not be, any more than mine is, up to meeting anything like the full demands of Kraus’s language without some help. It is, nevertheless, a full translation, and readable as such, though the limits of what it was intended to do should be born in mind.”

Russell’s translation has a wealth of detailed footnotes, illuminating things like the history of Viennese waste collection, Prussian Military officers and their uniforms, and in some cases providing entire poems or news reports that Kraus alludes to. In the corresponding website the footnotes are intended to be hyperlinked to the text, but this little feature doesn’t seem to have been implemented yet. Find them at the end of each chapter.

In addition to the website Russell has published his translation of the play’s epilogue, The Last Night, as a small indie press volume.

A third English translation, by Patrick Healy, has just been published in the Netherlands by November Editions.

Here is a very brief sample of the original and the four (including von Klot) translations, taken from the beginning of the epilogue. This particular example is in conventional rhymed stanzas, which is more characteristic of the epilogue then the text as a whole.

Kraus’s stage description reads (in one translation): Battlefield. Craters. Clouds of smoke. Starless night. A Wall of flame on the horizon. Corpses. Dying soldiers. Men and women with gas masks appear.

Then a dying solder cries out:

Hauptmann, hol her das Standgericht! Ich sterb’ für keined Kaiser nicht! Hauptmann, du bist des Kaisers Wicht! Bin tot ich, salutier’ ich nicht!

Wenn ich bei meinem Herren wohn’, ist unter mir des Kaisers Thron, und hab’ für sein Geheiß nur Hohn! Wo ist mein Dorf? Dort spielt mein Sohn.

When ich in meinem Herrn entschlief, kommt an mein lezter Feldpostbrief. Es rief, es rief, es rief, es rief! Oh, wie ist meine Liebe tief!

von Klot‘s “working translation” renders this:

Captain, go and fetch the court martial!

I do not want to die for an emperor!

Captain, you are the emperor’s jerk!

Once I’m dead I will no more salute!

When I’ve gone home to my Lord,

I will see the emperor’s throne far below

and I will laugh at his orders!

Where is my village? My son is playing there.

After my Lord has taken me away

my last field post letter arrives.

Oh, how they called and called and called!

Oh, how deep is my love!

Russell has:

Drum up the drumhead court martial, Captain!

Die for the Emperor? I will not! You’re only the emperor’s lickspittle, Captain; There’ll be no more salutes when I’m shot!

When I dwell with the Lord up in Heaven, Captain, And the emperor’s throne’s far away I’ll have only contempt for his orders, Captain Where’s my village? And my son still at play?

When I’ve peacefully passed to the Lord, Captain And my final postcard is read, Oh how my dearest ones call to me, call to me, How deep is my love, even dead!

Bridgham and Timms:

Captain, call out the firing squad! No one can make me shed my blood for King and Country. Go ahead, shoot! Once I’m dead, you can’t make me salute!

When I’m up there with the Lord on high, Kings and Emperors I’ll defy and scorn their Orders of the Day! Where is my home? Is my son at play?

While in the arms of the Lord I sleep, a letter scribbled on paper cheap will be read by a woman who starts to weep, aware of a love so deep, so deep!

and finally Healy:

Captain, call your court martials forth, I will not die for no emperor. Captain, you’re the emperor’s whore, I’m dead, and won’t salute no more.

When with the Lord I am at home Below I’ll see the emperor’s throne, and His commands I will disown, Where’s my village? There plays my son.

When as a fateful man I died, My last field post letter just arrived. It cried, it cried, it cried, O how deep this love of mine.